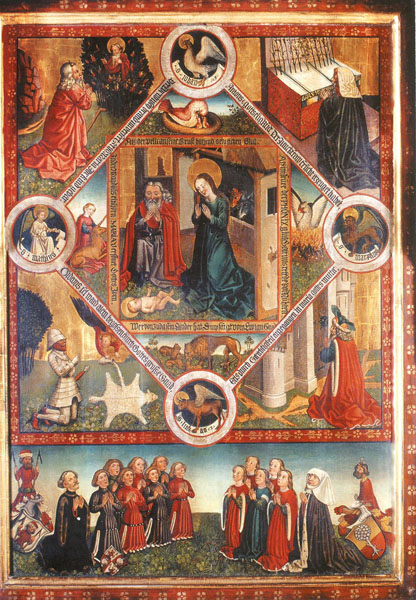

By permission from St. Sebald Church, Nürnberg

Donation of images to one’s local church was a frequent practice in the late middle ages. Such images are of major interest to the investigation of devotional practices and their instruments as they give quite vivid visual accounts of both bodily and mental practices of devotion while at the same time being devotional objects themselves.

In Nürnberg, Germany, a great number of epitaphs donated to the churches seem to have followed the same basic scheme. These epitaphs were divided into two parts; the upper ¾ of the image dedicated to a biblical or religious motive, and the bottom ¼ depicting the donator with his or her family. The epitaphs were simple, sometimes convex, panels positioned on the pillars facing either the nave or the aisles, or positioned on the outer walls of the church. Contrary to other visual materials donated to the churches (for example the stained glass windows in St. Lawrence church donated by various clergymen and the Keiserfenster by Emperor Frederick III and his wife), these panels seem to have been donated by regular citizens from Nürnberg.

The Starck epitaph from St. Sebaldus church dated 1449 is an illustrative example.

The upper part of the image is dedicated to a structure of different religious images with accompanying texts. The central image is a representation of the Birth of Christ which is surrounded by allegorical images, which can all be found in Physiologus and Medieval bestiaries, referring to both Christological and Mariological aspects of the birth; the unicorn referring to the Virgin birth and Incarnation; the Pelican who feeds its children with its own blood, an allegory of the passion of Christ and the Eucharist; the Phoenix, an allegory of the resurrection of Christ; and the lion of Juda or, according to Physiologus, the dead cups receive life when the old male lion breathes upon them, an allegory of the grace of Christ. The next layer of images consists of four Old Testament scenes. The textual interpretations are divided by small rosettes depicting the symbols of the evangelists and, thus, underlining the typological connection between the Old Testament and the New. The Old Testament motives are (beginning from bottom left) Gideon asking God for sign of victory, a prediction of the Virgin Birth; Moses with the burning bush, a reference to Mary’s purity; the flowering staff of Aron symbolizing the Virgin who gave birth to a child without having known a man (or as a version of Biblia Pauperum from around 1450 comments: ‘Hic contra morem producit virgule florem’); and Ezekiel before the closed gates of the temple, symbolizing that none other than God could enter the womb of Mary. The importance of the Virgin Mary is accentuated in this particular image.

The bottom ¼ of the image, which is clearly separated from the theological themes above by a painted boarder, shows the Starck family, all kneeling in prayer with their heads turned upwards. And, indeed, their bodily positions are perfect copies of the holy persons painted above: The central image of the Birth of Christ is in fact a scene showing Mary and Joseph kneeling in adoration of the newborn Child and, thus, their recognition of his divine identity. The four Old Testament scenes are all representations of kneeling persons. In copying the bodily practices of the biblical persons, the members of the Starck family not only take part in a universal practice of devotion, they also re-enact and re-actualize the devotion to and adoration of Christ. The devotional commemoration of past events makes the prototypical biblical adoration present, and the family becomes part of a long tradition. The devotional practices performed by the family members produce movements in three directions; it transports the members of the Starck-family back in time as well as it makes the past present and, last but not least, the image itself makes sure that the family is remembered in the future. Finally (hopefully), in the end the portrayed members of the family will be granted a place in heaven.

The devotional instrumentality of the Epitaph is perhaps hinted at in the image itself. Within the image, there is a subtle reference to a ‘dialogue’ between image and devotee: the upper part of the image is divided from the rest by a frame, thus simulating an image within the image. What the members of the Starck family is looking at is not the holy persons, but a depiction of the holy persons with its specific theological implications. When kneeling or saying a prayer in front of this image, the devotee would perform the same devotional practice as the Stark-family and the holy persons depicted and as a result become part of the universal practice of devotion. The epitaph Starck is arranged in concentric circles of devotion beginning with the adoration by the Virgin Mary and Joseph, thereafter revealed in the gospels, anticipated by nature/mythology (Physiologus), adored by the Old Testament figures, presented to the Starck-family and, finally, gazed upon by devotees visiting St. Sebald. The epitaph creates a sense of devotional community, not just here and now, but across boarders of time and space.