By Salvador Ryan

First published: ‘Resilient religion: understanding popular piety today’, in The Furrow (March, 2005), pp. 131-141.The web version is an abridged and slightly adjusted version of the article.

Web version: 10.01.2007

There is a story told about a boy who wanted a bicycle for Christmas and who prayed earnestly to God, promising, in return, that he would be good for a whole month. He soon thought better of pledging such a long period of virtue and revised it to a week and, finally, to a single day. Realising that he might not have the necessary resources even for that length of time, he chose an alternative approach. Seeing a statue of the Virgin on top of the mantelpiece he took it down and wrapped it in a towel, addressing God once more in the words ‘If you ever want to see your mother again …’ We may remember hearing such a tale recounted at parish missions or novenas, conducted by members of religious orders in our youth, or on other occasions as part of an homiletic ice-breaker. Yet, many may not realise that the story itself has a long history. In a poem entitled Bláth an Mhachaire Muire (Mary’s Field-flower) by sixteenth-century Irish bardic poet, Aonghus Fionn Ó Dálaigh, a version of this story appears in which a woman praying to the Virgin for the release of her son from captivity seizes the Child Jesus from a statue of the Virgin and Child as a pledge of his safety, enjoining upon the Blessed Mother to act quickly if she is ever to see her son again. The Virgin complies and the issue is resolved. Morality tales (exempla) such as these were common across Europe in the Middle Ages. In the late medieval popular mindset, the heavenly society was seen to work in much the same manner as the earthly one and being astute as children of this world guaranteed one’s efficiency at dealing with the community of light. What should be particularly noted, however, is the direct link between the present-day recounting of this story and the medieval period that spawned it. If the past is, indeed, a different country, there is no doubt that we have retained quite a lot of its vocabulary.

This article examines briefly how one might reach a better understanding of the current state of Irish popular devotion by exploring its roots in what preceded it. The predominance of the ‘Celtic Spirituality’ approach to Ireland’s devotional past has, sometimes unhelpfully, obscured the investigation of the history of Irish popular religion in the far more appropriate context of mainstream European piety. In an effort to highlight Ireland’s so-called distinctive spirituality, many commentators have often repeatedly missed the wood for the trees. Medieval Irish devotion (particularly after 1200) cannot be properly understood apart from its continued evolution across the European continent. Recent studies have demonstrated that the devotional mindset found in the heart of medieval Gaelic Ireland and expressed by the compositions of lay professional poets reflects a common heritage that was at home in Paris as it was in Portumna (a small town in Ireland).[1] Furthermore, this heritage was shared across lay and clerical and literate and illiterate lines.[2] The temptation to divide history into distinct periods where one or other kind of devotional outlook predominates can also lead to simplistic conclusions regarding the state of devotion today. It is far more important to recognise the resilience of certain devotions, even those that evolve over time into other guises. One could claim, for instance, that the efforts of the Irish mendicant friars to promote interiority of religion in fourteenth, fifteenth and sixteenth-century Ireland paved the way for the reforms envisaged by the Council of Trent: indeed so much so that when the Irish Franciscan friars at Louvain in the early seventeenth-century attempted to systematically inculcate Trent in Ireland by means of printed catechisms and other instructional works, very little of what they had to say was all that new.[3] Of course the Tridentine reform had a double task: firstly, to defend and re-affirm what was under attack by the Protestant reformers and secondly, to get its own house in order. Sometimes, there was a clash between both principles. Indeed, the Jesuits in seventeenth-century Ireland as elsewhere, while discouraging the use of dubious talismans by the laity, often replaced them with ‘official’ objects that worked in a very similar way. The use of the Agnus Dei (Fig. 1) is a case in point: A letter from the famous Irish Jesuit Henry Fitzsimon to the general of his order in the early seventeenth century, reporting on the efficacy of this sacramental, captures the enthusiasm with which such objects were promoted by Tridentine thinkers, provided they were in the right hands:

How many and how great miracles are worked by Agnus Deis can hardly be fully told. In the beginning of this Lent an elderly lady was, for three days, at death’s door, deprived of voice and memory. An Agnus Dei was hung round her neck and that instant she recovered her voice and memory, and the following day she was perfectly cured. It was refreshing to see the confusion of her heirs who, having prematurely taken away her goods, were forced to bring them back.[4]

Attempts at implementing the reforms of the Council of Trent in seventeenth-century Ireland were fraught with difficulty. Very often what was considered to be the ideal was sacrificed on the altar of practicality. For example, the official attitude of Trent to household religion, outside of the parish context, was one of suspicion, even going as far as to claim that such situations were seedbeds of subversion. Yet, ironically, in both Ireland and England, it was in the households of pious and learned recusants that the opportunities for the implementation of Tridentine norms such as frequent reception of the sacraments and satisfactory catechesis was most possible.

In fact, these households became, in the seventeenth century, almost quasi-parochial in themselves. A renewed emphasis on the necessity of intellectually-competent clergy was one thing. But, in reality, such candidates were difficult enough to find ‘on the ground’. That is why, in his tract on Penance, Sgáthán Shacramuinte na hAithridhe, written in 1618 in Louvain, the Irish Franciscan friar, Hugh McCaghwell, advised his audience that it was better for them to seek out a learned and wise lay person to be a spiritual director than an ignorant clergyman. The Irish catechisms produced on the Continent for ‘Trenting’ the native populace, more often than not, smacked as much of pre-Tridentine religion as that which it was supposed to replace. The attitude seems to have been one of ‘why try to feed with meat babies that are only capable of ingesting milk?’ Yet, equally, it must be remembered that the compilers of these catechisms had, themselves, been raised in a particular devotional environment before their period of study abroad and that the most Tridentine of clergy, if examined closely, possessed a traditional underbelly. Of course the implementation of reform was cut short in the mid seventeenth century and remained, in effect, interrupted, for the next two hundred years. Emmet Larkin’s thesis regarding the ‘devotional revolution’ in later nineteenth-century Ireland had its roots not only in systematic efforts at reform in the early seventeenth century but even earlier still. Indeed, the history of the Observant Franciscans from the fifteenth century onwards in Ireland is one of promotion of regular participation in the sacraments, the interiorization of religion and popularcatechesis. Interestingly, the very charges brought against both the Church and, in general, early and mid nineteenth-century Irish society, as described in Larkin’s thesis – the inept performance of clergy, the lack of attendance at the sacraments, poor catechesis, immoral living etc are almost carbon copies of the sort of reports that were made concerning late sixteenth and seventeenth-century Ireland. Coincidentally (or perhaps not), the remedies suggested also form a perfect match – sacramental practice, catechesis, good and well-trained clergy, the promotion of devotions such as the Rosary, novenas, sodalities and confraternities, the dissemination of catechisms, medals, agnus deis and the organisation of local missions.

|

| Fig. 3. A very inexpensive European aluminium medal from the 20th century. The adverse shows our Lady of the good councel, and on the reverse the guardian angel teaching a child to pray. |

All of these remedies can be found suggested and attempted in the work of the various religious orders working in seventeenth-century Ireland, in particular the Jesuits.[5] What made the efforts at reform in the later nineteenth century different from those in the seventeenth century was that they worked. Or, certainly, up to a point.

THE LEGACY OF MEDIEVAL RELIGION

One might imagine that twentieth-century popular devotion might have left behind its medieval legacy. Not so, however. Devotion to the Sacred Heart of Jesus, for which twentieth-century Irish Catholicism was ubiquitously famous, is a direct descendant of late medieval devotion to the side wound of Christ, which emphasised his love and mercy. Although devoid of the same explicit imagery of torture common to many medieval depictions, the Sacred Heart image appealed directly to the devotee to take refuge in the wounded heart of Christ. The Anima Christi prayer in the late sixteenth century, by including the petition “Within thy wounds hide me”, retained this image and linked it to the Eucharist just as countless medieval images had before it. Indeed, the proof of an effective image is the manner in which it continues to recur in the most unlikely places. Count Ludwig Zinzendorf, a Lutheran who set up a community for the Moravian Church at Herrnhut, Saxony in the eighteenth century, increasingly focussed his attention in the period 1750–60 on affective devotion to the Passion and an extreme form of blood piety, (Fig. 4), in the mould of the most elaborate of pre-Reformation devotees.[6] He was known to commission small drawings of the sinner huddled within the refuge of Christ’s heart wound that were designed to be carried on the person as relics. Perhaps the natural successor to the Sacred Heart image today is that of the Divine Mercy revealed to Blessed Faustina Kowalska. Once again, the rays of blood and water coming from Christ’s side figure strongly in this image and the emphasis is also on the receipt of Christ’s mercy and the salvation of souls.

Twentieth-century Catholic devotion may have liked to think that it was free of its medieval roots but in fact it wasn’t. Indeed, a quick perusal of the sorts of devotional reading material popular during this century very quickly indicates the opposite. The works of Alphonsus de Ligouri (1696–1787) although written in the eighteenth century, heavily rely on medieval exempla such as that recounted at the beginning of this article, both when speaking of the mercy of Christ and the intercession of his Blessed Mother. These works were reprinted again and again and proved to be hugely popular in the twentieth century. Similarly, the devotional works of the author known as E.D.M. (alias Fr Paul O’Sullivan OP, a well-known writer of devotional pamphlets) discussed the doctrine of Purgatory in Read me or Rue it by means of countless medieval stories of souls returning to loved ones looking for prayers of delivery. In his work on the angels, he states that an angel accompanies each person on the way to Mass, enumerating their steps in anticipation of a grand tot-up in Heaven. This idea figures prominently in the medieval list of benefits attached to attendance at Mass known as the merita missae which was hugely popular in late medieval Europe (Fig. 5) and is found in at least three Irish manuscripts from the fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries. Indeed, the reasons for attending Mass promoted by O’Sullivan almost match this list perfectly as do similar lists of promises attributed to devotions such as the recitation of the Rosary. These works can still be found advertised on a host of websites, proving their enduring popularity with twenty-first century devotees. Continued fascination with the extra-biblical aspects of the Passion of Christ lived on in the twentieth century in the promotion of certain Passion mystics such as Therese Neumann, Padre Pio and Gemma Galgani. Meanwhile, many prayer books of the twentieth century contained copies of the medieval Fifteen Prayers of St Bridget of Sweden (or Fifteen Oes) with their attendant promises to those who managed to recite them for a year and thus honour each wound that Christ suffered. Up to a point, these devotions were tolerated and even encouraged. However, the vivid and colourful nature of medieval devotion surviving in twentieth-century Ireland would not always be looked upon with such favour.

|

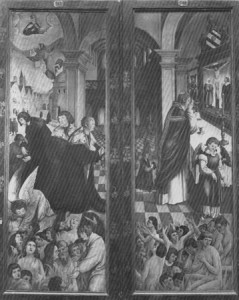

| Fig. 5. Holy mass, prayers and alms help the souls in purgatory, depicted on the wings of a German triptych c. 1520. |

POPULAR RELIGION IN IRELAND POST VATICAN II

In many ways the period immediately following the Second Vatican Council could be termed Catholicism’s version of the sixteenth-century ‘Stripping of the Altars’. (Fig. 6a-b) Interpretation of the decrees of the Council at local level were not always as successful as they might have been. What was perceived by many as church vandalism, to others as iconoclasm and to some as necessary reform, paved the way for a new mode of understanding liturgical space. In some quarters, the desire to rid churches of all manner of ‘clutter’ was accompanied by an equally fervent desire to rid devotional lives of its equivalent. Large and ornate Stations of the Cross were routinely replaced by neater and, almost invariably, aesthetically-inferior substitutes while popular devotions such as the Rosary were often frowned upon as the relics of a peasant spirituality that belonged to a different age. While most now agree that much of this knee-jerk reaction to the past bore no resemblance to the true spirit of the Council, the damage due to erroneous interpretations of change was considerable, particularly in Western society.

Although some initial efforts at the re-ordering of churches were a success, many others failed dismally. The decrease of emphasis on visual stimulation that was ubiquitous in the medieval period led, in certain cases, to the replacement of biblical scenes on stained-glass windows by amorphous multi-coloured designs that only individuals with PhDs in post-modernism might begin to interpret. The dispensing with ‘clutter’ of all sorts, including various statues and images, may have been intended to focus the worshipper’s mind more fully on the various movements within the liturgy itself, but it also succeeded in creating an atmosphere of sterility in what, for many, was as familiar a building as their own home. Indeed, the image of a home is useful in this regard. At the risk of an over-generalisation, one can compare older styles of worship space that were, indeed, cluttered and liturgically untidy, filled with congregations of individuals with equally untidy habits and ideas, with a family home, brimming with life: Messy? Yes. Dull? Never. Cramped? Yes. Higgledy-piggledy? Yes. Lived-in? Yes. Well-ordered? Rarely, perhaps. What happens when this space is re-ordered in such a way that it becomes too tidy and pristine to be familiar with and thus fails to retain that lived-in feeling? The house might remain tidy, but the children will not stay there. One might contrast the experience of attending liturgies in well-ordered churches in Ireland and the experience of an alternative variety of the Easter Vigil in Skopje, Republic of Macedonia. After the final blessing crowds of people throng the altar space, effectively hindering the bishop from processing down the aisle until he has blessed the many baskets of bread that are brought before the altar. Likewise, traditional painted hard-boiled Easter Eggs also need to be blessed. It will be a long night. There is a scramble; lots of hustle and bustle; but there is life. And there is fervour. These eggs will be given to friends, relatives and strangers, indeed to all whom the bearer meets and all will be greeted with the ancient proclamation ‘Christ is risen’ to which the receiver replies ‘He is risen indeed’. While the down-side of popular religion is often identified as a lack of order coupled with poor catechesis, one can never complain about its lack of fervour. In many parishes today there is often order in abundance; indeed a clinical sort of order; yet, many of these churches are virtually empty. Understood in the correct way, John Henry Newman’s observation that ‘a little superstition may be the price of making sure of faith’ is as challenging as it is alarming.

One of the problems with the denigration of popular religion lies in its misunderstanding of the term itself. In the past, ‘popular’ religion was equated with ‘folk’ religion, a quasi-heterodoxical form of piety associated with the unlearned and the lower social orders in general. However, this view has repeatedly been shown to be erroneous in recent studies.[7] A more accurate understanding of popular piety can be found in the etymology of the word ‘popular’ itself – ‘of the people’. The term does not specify certain social groups and is better understood as the personal engagement of individuals of all social groupings with the mysteries proclaimed from within official doctrine. This understanding will always be incomplete and, indeed, faltering. History has proved that remarkable theological insights were not always the preserve of the learned no more than heterodoxy was of the peasant. Doctrine and devotion walk hand in hand across the social spectrum and should not be considered rivals. A modern case in point is the late Karol Wojtyla (Pope John Paul II) whose philosophical and theological acumen could not be divorced from his traditional devotion to the prayers of his youth, such as the Rosary, and indeed his promotion of the image and prayers associated with Blessed Faustina Kowalska’s Divine Mercy devotion.

|

| Fig. 7. Divine Mercy: The version by Adolf Hyla, painted in 1943, particularly favoured by Pope John paul II. |

Devotion without doctrine may be mere sentiment but, equally, doctrine without devotion remains lifeless.

On the subject of liturgy and the ordering of churches, it is important that the Council’s exhortation to ‘noble simplicity’[8] does not collapse into the pursuit of something that merely engages the spirit and not the bodily senses. In the past, elaborate imagery engaged the eyes of worshippers; the use of incense also spoke to the senses. The burning of candles and the strains of plainchant all added to the sense of the sacred in the liturgy. This sort of ‘tangible religion’ spoke at many different levels, not relying solely on one’s spiritual disposition.[9] While the answer to the problem of the loss of the sense of the sacred in our churches is not simply to re-fill them with the clutter of yesteryear and expect the crowds to stream back, yet the lesson must be learnt again that the liturgical assembly of the broken body of Christ will not always make for neat liturgy. Indeed, as the Directory on Popular Piety and the Liturgy issued by the Congregation for Divine Worship points out: ‘lack of consideration for popular piety … often reflect(s) a quest for an illusory ‘pure’ liturgy which while not considering the subjective criteria used to determine purity belongs more to the realm of ideal aspiration than to historical reality’.

We may even be suspicious of the effects of the visual on worshippers. There is a story of a lady who came to the cathedral in Skopje, Macedonia, to pray that she might conceive a child. There are only two Roman Catholic churches in Skopje: the cathedral itself and a much smaller, wooden building in Bit Pazaar, the old Turkish quarter of the city. Arriving in the cathedral, the lady proceeded to walk towards the resident statue of the Virgin Mary to implore her to grant the request she desired. However, seeing that it was a statue of the Immaculate Conception, depicting the Virgin with her hands by her sides, she realised that this image was, in effect, childless. “You’re no use to me”, she muttered, before travelling on to the wooden church where there was a statue of the Madonna and Child. This was the appropriate image and that is where the lady decided to remain at prayer. We may be amused at what could be termed a simple or even undeveloped faith. However, deliberately choosing to direct her prayer towards an image of the Virgin as Mother is not as far removed from more ‘orthodox’ practices as we might like to think. Consider the many titles given to the Virgin in prayers such as the Litany of Loreto. Next consider how, at varying times, many devotees conclude their prayers with petitions such as “Seat of Wisdom, pray for us” when asking to be blessed when studying, “Mother of Good Counsel, pray for us” before making an important decision (cf. Fig. 3) or “Queen of Peace, pray for us” for harmony in their families and in the world. It has become quite natural even in officialdom to approach the Virgin in her most applicable guise. What the lady was doing in Skopje was not very different. In effect, when choosing to pray before the image of Virgin and Child in the little church at Bit Pazaar, she was saying “Joyful Mother with Child, pray for me …”

In the area of liturgy, increasing desensitisation to the meaning and value of symbolic ritual and gesture in the decades since the Council has contrasted, ironically, with the secular world’s rediscovery of it. It is interesting to note that today we live in an age where increasingly the visual message is becoming more important than the written one. If you study the phenomenon of modern advertising you will understand what I mean. Indeed, such is the power of the visual and symbolic nowadays that we are becoming increasingly adept at interpreting the messages we receive in this way. In many ways, our culture has never been more like that of the visually-rich fifteenth century than at present. Yet, ironically, the reduction of the importance of the symbolic and the visual in our churches has come at a time when we are perhaps most ready to interpret it. Could it be possible that the Church is one step behind secular culture in this regard? Furthermore, the engagement of secular culture with various discarded or virtually discarded aspects of traditional Christianity has reached new heights.

|

|

Fig. 8. An example of candle lights of basically secular remembrance: a Norwegian region commemorating all those killed or injured in 2006 on the roads in that particular region. A Norwegian local newspaper, Jærbladet, from 12th January 2007. |

While the churches were jettisoning candelabras and replacing them with push-button electric imitations (undoubtedly, partly for fire insurance purposes) the secular world was rediscovering the beauty of real candles and continues to do so, as a visit to your local town will undoubtedly demonstrate. While you may not have heard a sermon treating of the role of the angels in a while, the secular world has rediscovered these spiritual beings and has rehabilitated them in movements such as New Age. Gregorian chant, long since sidelined in parish churches has suddenly become popular again among many non-church going connoisseurs. Fasting, too, considered an optional extra by many within the Church today, has been rediscovered ‘outside’ the Church as a way to healthy living and balance in life. What is considered valuable at a popular level (and often regarded as peripheral at the level of Church hierarchy) always seems to find a way of seeping out and re-inventing itself in one way or another.

CONCLUSION

So, should the Church take its cue from the secular world and rehabilitate all that it has lost? One might suggest that the answer to this question should be both “yes” and “no”. The Church should certainly read the signs of the times and ask itself why practices that it has sidelined have simply not gone away. Perhaps it should realise that there is a certain sensus fidelium that can sniff out what is of value and that clings to it with tenacity. If it reviews its disregard for some of the elements of worship that it has formerly downplayed merely because the secular world is now enjoying them extra ecclesiam, then perhaps this is not the best reason. If, however, it digs deep into the richness of its tradition in search of practices of enduring value, then perhaps the tactic of recouler pour mieux sauter is the way forward. It seems philistine to continue to ignore what is a profoundly rich tradition. Late medieval spirituality, for all its shortcomings, depicted the things of Heaven in a manner that could be easily understood by contemporary secular society. That challenge remains today.

The future of popular religion in Ireland, as elsewhere, is assured. Whether it is practiced inside or outside ecclesial communities, it will remain and will develop in all sorts of shapes and forms. In order to better serve its people, however, the churches must not neglect the external elements and, in particular, the tangible elements of religion. By neglecting these ‘small things’, these ‘externals’ of religion, the larger things inevitably begin to crumble too. These elements give witness to something beyond ourselves. Popular piety gives life to our tradition for if there are no carriers of tradition, tradition ceases to exist.

[1] See especially Salvador Ryan, ‘Popular religion in Gaelic Ireland, 1445-1645’ (PhD thesis, National University of Ireland Maynooth, 2002), 2 vols.

[2] Idem, ‘The most contentious of terms: towards a new understanding of late medieval popular religion’, Irish Theological Quarterly 68 (2003), 281–90.

[3] Idem, ‘From late medieval piety to Tridentine pietism? The case of 17th century Ireland’ in Fred Van Lieburg (ed.), Confessionalism and Pietism: religious reform in the Early Modern period. Veröfentlichungen des Instituts für Europäische Geschichte (Mainz, 2006).

[4] Edmund Hogan (ed.), Distinguished Irishmen of the sixteenth century (London, 1894) 262.

[5] Emmet Larkin, ‘Devotional Revolution in Ireland 1850-1875’, The American Historical Review, 77 (1972), pp 644-5.

[6] For blood piety in late medieval Ireland see Salvador Ryan, ‘Reign of blood: aspects of devotion to the wounds of Christ in late medieval Ireland’, in Joost Augusteijn and Mary Ann Lyons (eds.), Irish History: a research yearbook (Dublin, 2002), 137–49.

[7] See, for instance, Carl Watkins, ‘“Folklore” and “Popular Religion” in Britain during the Middle Ages’, Folklore 115 (2004); also Salvador Ryan, ‘The most traversed bridge: a reconsideration of elite and popular religion in late medieval Ireland’, in Kate Cooper and Jeremy Gregory (eds), Elite and Popular Religion: Studies in Church History 42 (Woodbridge, 2006), pp 120-30.

[8] General Instruction of the Roman Missal Chapter 5, XII (279).

[9] See especially Salvador Ryan, ‘The quest for tangible religion: a view from the pews’, The Furrow (July / August, 2004).