EUROPEAN NETWORK ON THE INSTRUMENTS OF DEVOTION

EUROPEAN NETWORK ON THE INSTRUMENTS OF DEVOTION

© ENID Terms of use Contact Contact members of the network here

The coordinator can be contacted via e-mail |

Gallery

Devotional prints crossing denominational barriers

Apart from the obvious differences between Catholic and Lutheran religious life, the Lutheran devotional piety following Johann Arndt had several features in common with its Catholic counterpart. Or indeed, one might suggest that below current school theology a layer of devotional piety existed – to some extent shared by Catholics and Lutherans alike.In entirely Lutheran areas like in Norway, this emotionally charged devotion, often focusing on the Passion of Christ, created a demand that could not be covered by any Lutheran production. This resulted in a considerable import of Catholic imagery to a population which was by and large hostile to anything Catholic. In the later part of the 19th century in rural districts and along the west coast one would find an abundance of openly ‘Papist’ images, often oleographs, with the imprimatur of e.g. the bishop of Limburg. The Virgin Mary appeared often enough. The title of many such prints were in several languages, testifying to the concept of an international market. (HvA) Read more >>> |

Sculptures of the Virgin Mary on the exterior of houses

In towns and cities in Catholic areas, for instance in Flanders or Bavaria, you may find a Madonna sculpture on many a house corner, or above the main entrance. There are usually placed above the ground floor. To all who pass by, these ‘street Madonnas’ constant reminders of a spiritual world close by. They had their blooming in the 17th and 18th centuries – just like the (often painted) Madonnelle in Rome, of which there were still almost 3000 still extant in the middle of the 19th century. The images of the Virgin Mary are there to protect the house and the town, but also to awaken devotion in those who pas by, as they say a short prayer, a greeting, or at least by making the sign of the cross upon themselves. The sculptures are public displays of religion, keeping it constantly present, provoking devotional acts. In this respect they form part of a daily devotional practice, and they may therefore themselves be called ‘instruments of devotion’. (HvA) Read more >>> |

Dresses for Jesus and His Mother

In many Catholic churches we find statues of the Virgin Mary, with or without the Christ Child, dressed in magnificent robes and dresses. Sometimes the statues themselves are little more than a stand with head and hands, meant to be covered with a dress. These dresses change throughout the year, serving the possibility to change their appearance according to liturgical feasts or periods, sometimes probably simply for the sake of variety. To donate such dresses to the Mother of God and her Son was a sign of veneration, an act of respect and piety, in itself a devotion – and probably also developed into a pious competition between various donators. (HvA) Read more >>> |

Bruce Springsteen displaying a variety of religious medals

In the last ten years we have seen various devotional objects becoming fashionable. What used to be expressions of bad taste according to the stern protagonists of the Liturgical movement and the post Vatican II religious taste, or at least of an outdated religiosity, has suddenly become fashionable, perhaps related to the ‘shabby-chic’ genre. (HvA) Read more >>> |

Small Devotional Bronce Sculpture of the Post-World War II Generation in Germany

As contemporary art of the 20th century had left naturalism and realism behind in pursuit of new modes of representation and new forms, its development towards abstraction and of a new openness to various interpretations, presented religious art with a problem. The religious art, or devotional art, was an art ‘for’ somebody, and expressed the faith and devotion of a collective. What it stated was not subject to individual interpretation, its form language having to convey common beliefs, which means: the iconography and mode of contemporary art still had to be discernible by believers as expressing the faith of the Church.However, around 1920, the Liturgical Movement endeavoured to make more use of truly contemporary art, defining the current situation of the Church as embedded in its own time, while playing down the emphasis on tradition and history which had determined the religious position for so long. Through artistic beauty, Christianity should work pastorally to educate and edify, proclaiming a gospel which was relevant and authentic. The use of contemporary mode of representation was therefore regarded a necessity, a view by and large adopted by the second Vatican Council in its Constitution of 1963 on Sacred Liturgy. (HvA) Read more >>>

|

The ‘Irish Lourdes’

This photograph is of the ‘Irish Lourdes’, a cement and reinforced concrete replica of the grotto rock of Massabielle near Lourdes, France, where Bernadette Soubirous had 18 visions of the Virgin Mary in 1858. It is in the grounds of the church of the Oblate Fathers of Mary Immaculate in Inchicore, Dublin and became one of the most important Irish sites for public religious ceremony and devotion from the 1930s. (LG) Read more >>>

|

St. Jakobus d. Ä. in Trossenfurt c. 1925

Sometime in the 1920s, a photo was made of this church interior, seen from the nave towards its north-east corner and further through the chancel arch into the sanctuary with the main altar. The photo was used as the illustration on page 242 in the book Deutsche Volkskunst by Hans Karlinger, published in Berlin 1938.Visually noisy and overcrowded, this was exactly the kind of interior the Liturgical Movement campaigned against from the time around World War I. The endeavours to replace popular variety and ‘horror vacui’ with aesthetic simplicity, the bric-a-brac piety with ecclesial grandeur, had started in the 19th century with the sacred art of the school of Beuron in Germany. Just as later the Liturgical Movement, the Beuron endeavour was an assault on the bad taste which had resulted in pious items displaying the sweet Nazarene-early-Renaissance style now defined as ‘kitsch’. In fact, most revivalist endeavours searched for a unified, stylistically homogeneous, interior. (HvA) Read more >>> |

Icon painting monks in a Greek monastery

In a Swiss picture book, published in 1956, La Grèce éternelle, one colour photograph shows monks paintings icons in their studio in the monastery of Logovarda, founded in 1638 on the northern part of the Cycladic island of Paros, near the village of Naoussa. It still has a large library with some rare manuscripts. It is still ‘avanton’, meaning that the monastery with its two churches can only be visited by men.The photograph is interesting because it testifies to the dominance of western style in mid 20th century Greek icon painting. (HvA) Read more >>> |

The changing life of a devotional woodcut

In a period and a context where originality was rather unimportant, but where devotional quality played an important role, and where cutting of production costs was always attractive, illustrations in books were rarely or never subject to copyrights. Hence, a multitude of variations of the illustrations appeared: as originals, copies of originals, reversed copies, copies of copies or in various degrees of borrowing motifs, elements etc. Thus, an illustration could cross national borders, even denominational borders, or go from a public to a more private use – e.g. from a title page to a devotional picture or card. (HvA) Read more >>> |

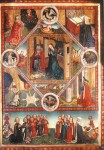

By permission from St. Sebald Church, Nürnberg Donated images and devotional practice

Donation of images to one’s local church was a frequent practice in the late middle ages. Such images are of major interest to the investigation of devotional practices and their instruments as they give quite vivid visual accounts of both bodily and mental practices of devotion while at the same time being devotional objects themselves.

In Nürnberg, Germany, a great number of epitaphs donated to the churches seem to have followed the same basic scheme. These epitaphs were divided into two parts; the upper ¾ of the image dedicated to a biblical or religious motive, and the bottom ¼ depicting the donator with his or her family. The epitaphs were simple, sometimes convex, panels positioned on the pillars facing either the nave or the aisles, or positioned on the outer walls of the church. Contrary to other visual materials donated to the churches (for example the stained glass windows in St. Lawrence church donated by various clergymen and the Keiserfenster by Emperor Frederick III and his wife), these panels seem to have been donated by regular citizens from Nürnberg.

The Starck epitaph from St. Sebaldus church dated 1449 is an illustrative example. (LS) Read more >>> |

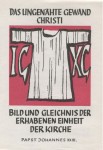

THE SACRED TUNIC IN TRIER – HEILIGER ROCK ZU TRIER THE SACRED TUNIC IN TRIER – HEILIGER ROCK ZU TRIER

The earliest mentioning of the sacred tunic of Trier, “heiliger Rock zu Trier” is the year 1196, when it was moved from elsewhere in the church and placed in the high altar. Supposedly, it was the tunic worn by Christ, “the tunic without seam, woven from top to bottom”, for which the soldiers on calvary cast lots, according to John 19,23seq. As the emperor Maximillian in 1512 insisted on seeing it, the altar was opened, and after this the public demand to see it as well resulted in an annual display, and from then the tunic became the goal for a great many pilgrims.

However, soon it was put on display much less frequently. In 1844 half a million pilgrims gathered to visit the tunic, in 1891 one million, and in 1933 more than two millions. In 1959 the tunic was put on display above the high altar from 19th July to 20th September, in which period it was seen by 1, 8 million pilgrims. ( HvA) Read more >>> |

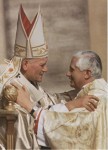

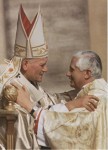

POPE JOHN PAUL AND CARDINAL JOSEPH RATZINGER POPE JOHN PAUL AND CARDINAL JOSEPH RATZINGER

Postcard, bought in Rome, November 2005. On the back of the photo, from the newspaper Osservatore Romano, the following description appears in Italian: “22 ottobre 1978. Il saluto di obbedienza del cardinale Joseph Ratzinger al neoeletto papa Giovanni Paolo II durante la messa di inizio pontificato”, meaning: Cardinal Ratzinger offering the newly elected pope John Paul II his greeting of obedience during the mass marking the beginning of the new pontificate.As Ratzinger was elected to succeed John Paul II as pope, this old photograph from 1978 gained a new importance, precisely in the period of transition from the old to the new pontificate, contributing to transfer authority and benevolence from the old to the new pontiff.Therefore, it was only natural that the Sankt Ulrich Verlag of the diocese of Augsburg used that very same photograph as book cover in 2009, when it published Pope Benedict’s book on his predecessor, titled: “Johannes Paul II. Mein geliebte Vorgänger”, John Paul II. My beloved predecessor. (HvA) Read more >>>

|

The miraculous medal The miraculous medal

On 27 November 1830, Catherine Labouré, a young novice with the Daughters of Charity of St. Vincent de Paul residing in Rue du Bac in Paris, had one of a series of visions. Virgin Mary appeared to her, telling her to have a medal made after the model she showed her, and promised that those who wear it would receive great graces. (EHS) Read more >>> |

THE DIVINE MERCY IMAGE THE DIVINE MERCY IMAGE

A new devotional motif has emerged towards the end of the 20 th century, Christ as Divine Mercy, according to a 1931 vision of the Polish St. Maria Faustina Kowalska of the Most Blessed Sacrament (1905-38), sister of Our Lady of Mercy in Cracow.Her diary, written between 1934 and 1938, “ Divine Mercy in My Soul”, has become the very handbook for devotion to The Divine Mercy. In the book she records her visions (from 1931 onwards), her thoughts and her prayers. Through intervention of the archbishop of Cracow in 1978 an ecclesial ban on spreading the message was lifted, the archbishop was later that year to become pope John Paul II, who two years later wrote an encyclica on Divine Mercy, Dives In Misericordia . Since 1944 the devotion had become increasingly popular in America, and in 1965 the informative process was already initiated. Promoted by the pope and the hierarchy, and not least due to its popularity in USA, the devotion spread rapidly. In 1993 Sr. Faustina Kowalska was beatified, and eventually, in 2000, she was canonized. In accordance with Christ’s wish expressed in one of Sr. Faustina’s visions, Sunday after Easter was then formally announced as henceforth Divine Mercy Sunday. (HvA) Read more >>> |

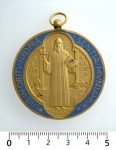

THE MEDAL OF SAINT BENEDICT THE MEDAL OF SAINT BENEDICT

In 1880 the 1400th anniversary of the birth of Saint Benedict was celebrated. For that occasion a medal was designed, a medal which has been struck continuously since, under the supervision of the monks of Monte Cassino. It is known as the Jubilee Medal, and two versions of it are shown in the pictures. The design of the Jubilee Medal is based on older elements. (EHS) Read more >>> |

DEVOTIONAL CARDS / HOLY CARDS DEVOTIONAL CARDS / HOLY CARDS

Devotional cards, or holy cards, were often used as small presents to commemorate important religious events, offered either by friends and family, or by the person involved (e.g. Ordinations or professions). They were also used as pious bookmarks in prayer books or other devotional literature. Another kind propagates the sainthood of a certain person, or cards with prayers and depictions of saints are bought at sanctuaries, pilgrimages etc.In terms of use and iconography, combinations texts-pictures, and the choice and mode of reproductions of works of art, this type of cards, going back several centuries, constitutes a vast and interesting group of devotional instruments. As with so many other such instruments, the possibilities provided by new means of mass production in the 19 th century resulted in a huge and ever more diverse body of such cards.The actual use of such small, pious cards is testified to by the practice of St. Therese of Lisieux, documented in Pierre Descouvemont and Helmuth Nils Loose: Therese and Lisieux, Toronto 1996, reprint 2001, ISBN2-89507-214-0. See also the richly illustrated publication on such cards, Angelika Pürzer: Das Andachtsbild. Frömmigkeit im Wandel der Zeit , St. Ottilien, Eos-verlag 1998, ISBN 3-88096-581-1. As far as I know, a scholarly presentation and interpretation of this particular group of instruments in a devotional perspective still remains to be written. (HvA) Read more >>> |

Part of the wall of ”Juliet’s house” in Verona, photographed on 28th October 2004 Part of the wall of ”Juliet’s house” in Verona, photographed on 28th October 2004

During the Bologna-workshop we had a somewhat unexpected opportunity to experience two modern, non-religious devotional practices. The first one, in Padova, was the “choreography” connected with visiting the frescoes of Giotto in the Arena Chapel. To behold this famous work of art, one had to wait outside, then being let in, 25 at a time, to watch a video explaining the chapel, then, after 15 min., the outside air having been purified, let in to see the actual chapel for another 15 minutes, then out again through another air lock. Visiting St. Anthony was a rather simple operation compared to the trappings of this aesthetic pilgrimage!The other modern, secularized “devotional” practice was the thousands of small scraps of paper attached to the so-called “Juliet’s house”in Verona. The name of the loved one was written on them, or hope expressed that they would stay together, or that some loved one would return the love, or poems etc. The practice was not much different what you may experience at some religious place, even though everybody knows that Juliet is a fictional person, and that this house rather recently was picked out to be the house of Juliet (a balcony attached, of course). Each year all the scraps are removed, and during the coming year new ones then cover the walls.Both examples are just of modern, quasi-religious devotional practices, are extremely interesting, telling us much about contemporary phenomena of non-religious devotional practices, as well as about the roles played by art and mass tourism.So, even if traditional Christian devotion plays a lesser role in modern secular society, the need for collective ‘devotional’ practices or secular ‘shrines’ to be visited, seems to remain. The media create a contemporary global awareness where celebrities serve as heroes or heroines, idols or, indeed, secular ‘saints’. This could be observed around the death and afterlife of Elvis Presley since 1977, it became abundantly clear as Princess Diana died in 1997, and again at Michael Jackson’s death in 2009.One further example is the shrine in remembrance of Michael Jackson erected in the city centre of Munich, Germany, in the autumn of 2009. Using an existing monument over another singer and composer, fans of the deceased artist and performer covered it with letters, pictures and objects as a farewell gesture to Michael Jackson. Many of the objects and pictures were actually religious, like pictures of Divine Mercy, Lourdes-figurine, crosses, angles etc. (HvA) View pictures >>> |

Glass painting from the church at Os, outside Bergen, Norway. Painted en grisaille ca. 1660. Glass painting from the church at Os, outside Bergen, Norway. Painted en grisaille ca. 1660.

The Danish two-liner reads: ”Gud os I Moders lif til dette lif har dannit Oc med sit ord oc aand til ævigt lif opammit”.

Which means: For this life, God has created us in the womb of our mother, And with his word and spirit nurtured us to eternal life.

To illustrate this point, Christ is depicted as a painter in front of his easel, painting (a) man. This visual metaphor was not unusual, as instances are known where the devout Christian was depicted, painting Christ or godly things in his or her heart in much the same way as Christ is shown painting (i.e. creating) a human being. In such cases the heart is a canvas on an easel as depicted by Hendrick Goltzius in an engraving, “Exemplar Virtutum” from 1578, the Christian (anima humana) represented as a painter copying the Christ Child in her heart, with the quotation from Ephesians 5,1: “Therefore, be imitators of God, as beloved children”. This way of rendering the ‘imitatio Christi’ is also found in an engraved illustration in Antoine Sucquets: “Via vitae aeternae”, published in Antwerp 1620. Here the painter is contemplating a Nativity scene, and then painting the salvific consequences of that event in a human heart.

It is important to notice that the glass painting depicts Christ creating “ex nihilo” as it were, not copying or portraying something. While creation as such belongs to God, imitative and meditative activities, but not creative, belong to the devout Christian, who in this way can show what fills his or her heart through the imitation of Christ.

To be able to execute this kind of glass painting, copying from an engraved model of some kind, perhaps an emblem, was expected of a glass maker in the 17th century. As stated by the rules of 1684 for the glass makers’ guild in Bergen: «Naar nogen Glarmester skal i Lauget antages, da skal hand først giøre sit Mester-stykke, Nemlig: En Bibelske eller anden Historie, Ridset og Brændt paa Glas, og et dygtig stærk Vindue», which means: If any man should be accepted as a member of the guild, first he must make his master piece, which is: a biblical or other story, drafted and burnt on glass, and a good, strong window. (HvA) View pictures >>> |

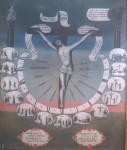

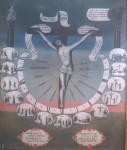

«Passion Clock» (Passions Wisere), anonymous workshop, 18th century «Passion Clock» (Passions Wisere), anonymous workshop, 18th century

Painting in Langestrand church in Larvik, Vestfold, Eastern Norway. According to a secondary inscription on the painting itself, it was donated to the church by a Knud Mørch in 1752, which thus provides a ‘terminus ante quem’ concerning the dating of this painting.

This particular motif, found in a number of Danish and Norwegian churches, is an example of pious Lutheran concentration on the Passion of Christ, obviously influenced by Pietism. We know of a number of almost identical paintings, as well as a number of Swedish woodcuts. The paintings date from the period 1730-60, the woodcuts are somewhat later. There are 17th century German engravings with a similar iconography, but the model of the Passion Clock paintings has not yet been found.

As one can see on the picture it consists of a crucifix, small scenes from the Passion arranged along the face of a clock, and with a certain element of texts in the painting.

As I am preparing a book on this motif, I wound be very interested in learning about any even remotely similar iconography outside Scandinavia. (HvA) View picture >>> |

Engraved frontispiece of Het geestlyck kaertspel met herten troef, oft het T’spel der liefde, by Joseph of St. Barbara OCD Engraved frontispiece of Het geestlyck kaertspel met herten troef, oft het T’spel der liefde, by Joseph of St. Barbara OCD

Published by Andreas Paulus Colpyn in Antwerpen, 3rd edition ca. 1700. The preface is dated 10th June 1666. The book was published in Flemish.

“The spiritual game of cards with hearts as trump, or the game of love”, according to the author himself goes back to a homily delivered in 1661. He then uses the metaphor of a game of cards to educate the reader in how to play well, which means how to live a good, pious and devote Christian life, and thus winning the great price: eternal bliss. Even though a number of the engravings depict a monastic setting, the fact that Flemish was used, and even quotations given in Flemish with the Latin text as foot notes, made the edificatory book possible to use by devoted lay people and not just by Carmelite fathers and nuns.

The book is illustrated with 14 copper engravings, one for each of the cards of hearts, providing an abundance of heart symbolism. The frontispiece carries the small inscription “Fred Bouttats fe”, identifying the Antwerp engraver Frederik Bouttats the Younger (1610-76).

This particular 3rd edition is not mentioned in the standard bibliography by John Landwehr, Emblem Books on the Low Countries 1554-1949, Bibliotheca Emblematica, vol. 3, Utrecht 1970, no. 171-175. Another third edition, 1712, is mentioned as no. 273, but by another publisher. Landwehr suggest the year of the first edition might be 1676, but it is possible that there was an earlier edition 1666-67, which would make less of a gap between the preface and the consents of 1666 and the actual publishing. According to Landwehr, the “Derden Druck” on the title page occurs on both 3rd edition of 1712, and on a few years younger 4th edition.

This 4th edition had the illustrations outside the pagination, where as our copy has pagination engraved on the plates itself, but not the correct numbers. They seem to have been taken from an earlier edition with paginated illustrations, and the reused here without changing the numbers on the plates. Thus, our edition was probably published between 1690 and 1715. (HvA) View picture >>> |

Christ Child altar, painting on canvas, Bergen Museum inv.no. NK 539, height: 81,5 cm, width: 56 cm Christ Child altar, painting on canvas, Bergen Museum inv.no. NK 539, height: 81,5 cm, width: 56 cm

This Christ Child altar is a painting on canvas with a hole in the middle into which is inserted a kind of Christ Child doll, made of cardboard, silk and paper, placed under a canopy of real velvet. It is possible that the three dimensional Christ Child was inserted secondarily, as it covers parts of the painting once obviously meant to be seen.The picture, Bergen Museum inv.no. NK 539, height: 81,5 cm, width: 56 cm was probably made in Austria ca. 1750, a so-called “Kloster Arbeit”, which means a devotional object produced by cloistered nuns in a monastery.

The motif is a Baroque altar with the Christ Child surrounded by putti, possibly a copy of the Loretto-Kindl-altar, erected in 1731 in the in the church of the Capuchin nuns in Salzburg, soon becoming a very popular “Gnadenbild”. It was destroyed by fire early in the 19th century.

Such pictures were probably meant for devotional purposes in the homes of wealthier families. For any informations on similar pictures, the Church art collection of Bergen Museum would be most grateful. (HvA) View picture >>> |

S. Margarita da Cortona S. Margarita da Cortona

(Bergen Museum, inv.no. By 7957) Copper engraving, 217 x 165 mm, late 18th or early 19th century, with a 19th century rather rude hand colouring. The picture came to University museum in February 1893 as a gift from Ole Fredrik Knudsen who worked as an artisan in Bergen, a woodcarver.According to the inscription below the picture, «A. Russo f.[ecit]» it was made by a A. Russo, about whom not even Thieme-Becker has anything to say.This kind of pious graphic sheets, here depicting the patron saint of the penitent, were presumably sold at modest prices in large numbers to adorn the living rooms of ordinary people. As S. Margarita, who died in 1297, was not canonized until 1728, this date is the ‘terminus post quem’ concerning the dating of this picture.The crude colouring offers the opportunity to reflect on the strong colours of much folk art, as contrasted with the engraving itself. Apparently little was cared about a detailed colouring following the engraved figures. Of course, strong colours were also necessary simply to compensate for the lack of light in the homes of most people. (HvA)

View picture >>> |

|